Shorelark, one of my all time favourite birds. But first a word about their name. For the British birder “Shorelark” seems perfect, as we only come across this species on the coast in winter, or more rarely in coastal-type habitats, such as the edges of inland reservoirs. But across their global range, these are mountain birds. Only the European subspecies flava spends any time on the coast, so the name Horned Lark is much more appropriate: in their breeding plumage across their whole range these birds have fabulous black horns. However, all my formative associations with this species are connected with the British name “Shorelark”. As such I shall refer to “Shorelark” when describing the European subspecies flava and use the term “Horned Lark” for all other forms. It is a personal thing!

As a boy I can remember studying pictures of Shorelark, of seeing their amazing horns and their yellow-and-black patterned head. On reading that these birds could be found on the Norfolk coast in winter, I immediately started dreaming of a visit to Holkham Bay. Being a young teenager with no income, it seemed impossible that I would ever get to such a remote place. But I worked out that if my paper round could somehow pay for my train ticket, then I could sleep in the bird hides at Cley and make my winter dreams come true. I even got as a far as persuading my parents to let me practise sleeping in the shed in our garden on a bitter winter night, as preparation for my nights in the Norfolk bird hides. I think I made it to about 10:30pm on the first night before the freezing feel of sleeping on concrete drove me back inside.

It was some years before I made it to the north Norfolk coast and fortunately I never had to endure a night in the hide to do so. My early notebooks record my most memorable UK Shorelark experience, a close encounter with a flock of 32 in front of the dunes at Holkham Bay. I crept out alone onto the freshmarsh before dawn and waited for daylight. As light arrived a large mixed flock of birds flew in and landed right in front of me. Scanning through the flock I came across the Shorelarks, which were feeding together with Twite and Goldfinches. In those days special moments were recorded on paper in the form of some rather dodgy drawings, rather than by camera:

Not only was this a memorably close encounter, but once in a while the flock would fly up and circle around me, the air filled with calling Shorelarks, before settling down to feed once again.

Sounding something like this:

Audio Player

[Matthias Feuersenger, XC41283. Accessible at www.xeno-canto.org/41283]

When I was young it seemed impossible to imagine that one day I would travel widely, often just to look for birds. I have always been drawn to the mountains and so, as life turned out, I have come across Horned Larks in many countries and in many different forms. This week Dave Lowe got in touch and asked if I would be interested in joining him to go and see what is widely regarded as an individual of the North American form of Horned Lark which has somehow found it’s way to Staines Reservoir in Surrey. I believe that this bird is suspected of being of the form hoyti, from the north central part of the North American range, breeding on arctic islands. Neither Dave nor I travel to see birds out of the county much these days, but a nearby vagrant Horned Lark would be a treat. Dave, incidentally, was also the finder of the Farmoor Reservoir Shorelark, some years ago.

Last Saturday afternoon at Staines Reservoirs in late January was dark, with gusting wind and rain showers. The Horned Lark was present, but was feeding some distance away on the west shore. We could make out that the bird we were looking at was a Horned Lark, but seeing the finer plumage details were impossible at that range. Fortunately others have had closer views, so I have borrowed a image from fellow Oxfordshire birder Ewan Urquhart:

©Ewan Urquart, his blog post is here.

Horned Lark taxonomy is changing rapidly. This paper splits Horned Lark into five palearctic species and one nearctic species. Never needing a second invitation to look at my Horned Lark pictures, I’ve dug out a few images from various locations over the years for comparison:

American Horned Lark, Eremophila alpestris alpestris, Rocky Mountains, Jasper, Alberta, Canada, June 2013. Many subspecies of Horned Lark have been described from North America and their distinction and identification is not fully understood. Future DNA studies may help clarify the situation. This bird was in the far west of North America, high up in the Rockies, so would not be expected to bear a close resemblance to the bird at Staines Reservoirs. The ground colour to the face and throat is white with no yellow, although many other nearctic forms inlcuding hoyti, do have yellow in these areas. The eye mask is clearly separated from the throat patch. The mantle feathers are dark centred on this bird, creating a streaky and contrasting feel to the upperparts. There are pinkish tones to the nape and lesser covert feathers.

Shorelark, Eremophila alpestris flava, Hardangervidda National Park, Norway, May 2008. A European bird on it’s Scandinavian breeding grounds. This is a bird of the population that are thought to winter on the English east coast. There is an intense yellow to the forehead, supercilium and throat, the black eye mask does not extend below the ear coverts. The lesser coverts are not noticeably pinkish.

Atlas Horned Lark, Eremophila alpestris atlas, Oukamedian, Atlas Mountains, Morocco, April 2008.

Perhaps my favourite form of Horned Lark. In spring these birds have dense black eye masks, that curve down to nearly meet the large black throat patch. There is a slight yellow wash on the throat and forehead and best of all a lovely pinkish-rufous nape that contrasts with the light grey back. The upperpart feather tracts have slightly dark centres, but this does not create a very streaky or contrasting pattern to my eye. Compare the upperparts on this bird with those of the American Horned Lark above.

Caucasian Horned Lark, Eremophila alpestris penicillata, Caucasus Mountains, Kasbegi, Georgia, April 2013

In the form pencillata the black eye mask extends down to meet the black throat patch. The throat and forehead are slightly washed with yellow and the nape is pinkish in colour. The lesser coverts and mantle are greyish in colour without much streaking or contrast.

Sogut Pass, Taurus Mountains, Turkey, May 2007

This bird, below, from south-west Turkey is also of the form pencillata and shows much black on the head and throat. The eye mask extends down from the eye to join the large black throat patch, which extends up onto the lower throat and is more extensive than that in the forms above. This was a particularly horny bird!

Horned Lark, Eremophila alpestris elwesi, Tibetan Plateau, near Zioge, Sichuan, China, May 2015

Much further east there is little yellow on Horned Larks. This bird was feeding in late afternoon sun at 3500m in a restaurant car park. The ground colour to the face is white, not yellow. The eye mask and throat are clearly separated by white. The lesser coverts and nape had a light brown tone (maybe a hint of pink?). As I lay flat out on my front photographing this bird, it ran straight past my right shoulder to take a breadcrumb from the road behind me.

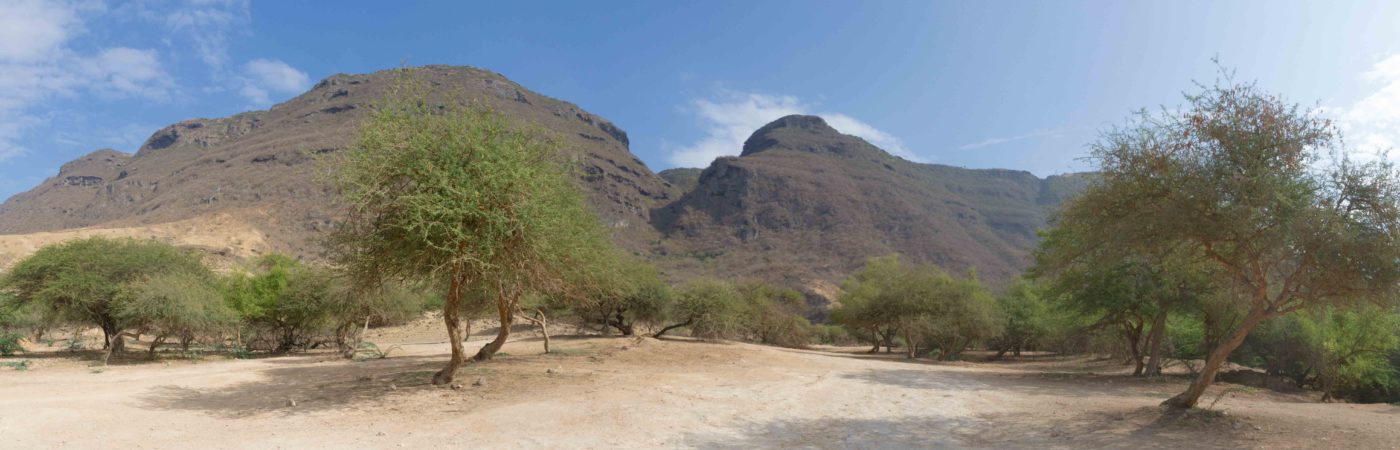

Temminck’s Lark, Eremophila bilopha, Tagdilt track, Morocco, April 2008. A monotypic species from north Africa and the desert cousin of Horned Lark. Superficially similar to the elwesi subspecies of Horned Lark from China, see above, with no yellow on the forehead or throat. However the throat band is much thinner and the upperpart colouration is a rich desert brown, perfectly matching it’s habitat.

I still think Horned Larks are fabulous birds. They not only provide much interest with their subtle plumage variations across their enormous range, but they are beautiful birds found in very special places and that is part of their appeal.